Thưa Ban biên tập!

Tôi thường được nghe câu “Một con chim trong tay đáng giá bằng Hai con chim trong bụi rậm”

Warren thường hỏi rằng có bao nhiêu con chim trong bụi rậm, lãi suất chiết khấu là gì và mức độ chắc chắn của bạn là bao nhiêu ?

Theo tư duy của tôi là, ví dụ cổ phiếu A nào đó, tôi cho rằng có khả năng là có chim, đang bán với PE hiện tại là 10 lần, tôi tính rằng tốc độ tăng trưởng là 15%/năm. Thì 5 năm sau tôi bắt được 1 con chim (thu hồi vốn).

Và tôi kết luận là: Lãi suất chiết khấu mà Warren nhắc đến ở đây có phải là con số 15% tôi đang nói ở trên hay không?

Khi nào? Có phải là con số 5 năm tôi nói ở trên hay không?

Tôi thực sự không chắc chắn với lối tư duy đó của mình nên nhờ đến BBT giải thích kỹ giùm tôi. Tôi rất cám ơn BBT.

Chúc BBT nhiều Sức khỏe, Hạnh phúc và Thành công !

Vâng cám ơn câu hỏi rất hay của anh, chúng tôi háo hức được biết quý danh của anh:

Đúng như anh đã nhớ chính xác câu thành ngữ của triết gia Aesop và đoạn văn của ngài Buffett về câu thành ngữ nầy, chính xác là trong bức thư thường niên gửi cổ đông Berkshire Hathaway năm 2000 (linK: https://newslettervietnam.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/TGN-2000-Berkshire-Hathaway-letter.pdf), ngài Buffett đã nói rằng – chúng tôi xin trích nguyên văn bằng Anh ngữ:

“The oracle was Aesop and his enduring, though somewhat incomplete, investment insight was “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” To flesh out this principle, you must answer only three questions:

(1) How certain are you that there are indeed birds in the bush?

(2) When will they emerge and how many will there be?

(3) What is the risk-free interest rate (which we consider to be the yield on long-term U.S. bonds)?

If you can answer these three questions, you will know the maximum value of the bush ¾ and the maximum number of the birds you now possess that should be offered for it. And, of course, don’t literally think birds. Think dollars. Aesop’s investment axiom, thus expanded and converted into dollars, is immutable. It applies to outlays for farms, oil royalties, bonds, stocks, lottery tickets, and manufacturing plants. And neither the advent of the steam engine, the harnessing of electricity nor the creation of the automobile changed the formula one iota — nor will the Internet. Just insert the correct numbers, and you can rank the attractiveness of all possible uses of capital throughout the universe.

Common yardsticks such as dividend yield, the ratio of price to earnings or to book value, and even growth rates have nothing to do with valuation except to the extent they provide clues to the amount and timing of cash flows into and from the business. Indeed, growth can destroy value if it requires cash inputs in the early years of a project or enterprise that exceed the discounted value of the cash that those assets will generate in later years.

Market commentators and investment managers who glibly refer to “growth” and “value” styles as contrasting approaches to investment are displaying their ignorance, not their sophistication. Growth is simply a component ¾ usually a plus, sometimes a minus ¾ in the value equation. Alas, though Aesop’s proposition and the third variable ¾ that is, interest rates ¾ are simple, plugging in numbers for the other two variables is a difficult task. Using precise numbers is, in fact, foolish; working with a range of possibilities is the better approach.

Usually, the range must be so wide that no useful conclusion can be reached. Occasionally, though, even very conservative estimates about the future emergence of birds reveal that the price quoted is startlingly low in relation to value. (Let’s call this phenomenon the IBT ¾ Inefficient Bush Theory.) To be sure, an investor needs some general understanding of business economics as well as the ability to think independently to reach a well-founded positive conclusion. But the investor does not need brilliance nor blinding insights.

At the other extreme, there are many times when the most brilliant of investors can’t muster a conviction about the birds to emerge, not even when a very broad range of estimates is employed. This kind of uncertainty frequently occurs when new businesses and rapidly changing industries are under examination. In cases of this sort, any capital commitment must be labeled speculative.

Now, speculation — in which the focus is not on what an asset will produce but rather on what the next fellow will pay for it — is neither illegal, immoral nor un-American. But it is not a game in which Charlie and I wish to play. We bring nothing to the party, so why should we expect to take anything home?”

Như vậy, ngài Buffett đưa ra 4 luận điểm trong đoạn văn bàn về định giá và thành ngữ nổi tiếng của Aesop nầy:

– Thứ nhất, để đánh giá được liệu đàn chim trong bụi có xứng đáng để ta đầu tư, ta cần biết có bao nhiêu chú chim trong bụi (tức dòng tiền mỗi năm của công ty là bao nhiêu), và chúng sẽ xuất hiện khi nào (thời gian của dòng tiền) và lãi suất phi rủi ro (lãi suất chiết khấu).

Anh chưa hiểu bản chất của lãi suất chiết khấu anh sẽ phải đọc lại công thức về chiết khấu dòng tiền (discounted cash flow). Ví dụ 1 tỷ thu nhập năm 2019 sẽ có giá hơn rất nhiều so với 1 tỷ thu nhập năm 2029: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/dcf.asp

– Thứ hai, ông cho rằng phân biệt “growth” với “value” không có ý nghĩa vì “growth” là một thành tố để tính ra value của doanh nghiệp.

– Thứ ba, ông cho rằng giá trị thực của doanh nghiệp thay vì là một điểm chính xác thì nên là một vùng xác suất (range of possibilities) rộng – khá giống với thứ vùng giá trị thực mà chúng tôi đã làm từ trước đến nay theo lời dạy của ngài Graham, khiến rất nhiều độc giả khó hiểu. Ông giải thích rằng chỉ 0.75% thay đổi (3/4) trong lãi suất chiết khấu phi rủi ro thì đủ làm định giá của chúng ta thay đổi đáng kể…

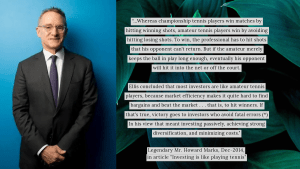

– Cuối cùng, ông cho rằng trò chơi đầu cơ – thay vì phân tích xem giá trị thực của mình nhận về so với giá cả bỏ ra – lại tập trung vào việc bán cho kẻ sau với giá cao hơn mình đã mua – là một trò chơi mà cả ông lẫn ngài Munger không muốn chơi.

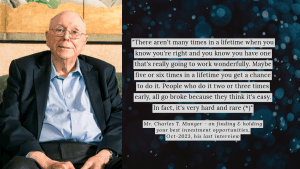

Đó là luận điểm của ngài Buffett. Còn anh hỏi công thức DCF thì rất phức tạp, chúng tôi cũng ít khi dùng trừ một số case bất động sản mà có dòng tiền dễ dự đoán. Đối với những NĐT cá nhân chúng tôi cho rằng phương pháp không trả giá qua cao (“do not pay too much”) của ngài Graham là một phương pháp hữu dụng hơn cả. Nếu anh hỏi sâu hơn thì chắc chúng tôi phải hẹn anh một ấn phẩm khác để nói sâu hơn vậy…

Một lần nữa cám ơn câu hỏi hay của anh và mong được biết quý danh của anh.

Team S.A.F.E